Introduction

Walter Benjamin’s unfinished Arcades Project (1927-1940) possesses a surplus of informational apparatuses that seem to announce the work’s indexical imagination as one blasted out of the continuum of history into the present experience. Readers encountering the text are faced with the task of navigating through Benjamin’s over-1000-page experimental historiography on nineteenth century consumer-capitalism via thousands of discreet quotes, ordered in one of Benjamin’s “Konvolutes,” and assembled in a “literary montage,” as evidenced by an excerpt from Konvolute A:

The newest Paris arcade, on the Champs-Elysées, built by an American pearl king; no longer in business. – Decline – [A2,3]

Toward the end of the ancien régime, there were attempt to establish bazaar like shops and fixed price stores in Paris…. The have undergone a great deal of development since 1870 and they continue to develop E

Levasseur, Histoire du commerce de la France, vol. 2 (Paris, 1912) [A2,4] Arcades as origin of department stores? Which of the margins named above were located in arcades? [A2,5]

The effect is one that plays with both narrative flow, the cinematic experience of information, and informational labels themselves, and the project is a collection that resembles one part bibliography, one part history, and one part personal journal. The sheer amount of data is massive and from the metadata on each individual entry to the use of what Susan Buck Morss describes as a “keyword system”1 for labeling the Konvolutes, The Arcades Project centers on the question of what it means to read and experience historical data.

Benjamin’s overt interest in the question of organizing knowledge makes him an obvious touchstone for scholars of information technologies. In the fall of 2012, as part of a seminar on the history of research, “Bad Research and Information Heresies,” I created a website that documented and tagged these various kinds of information technologies that Benjamin employed in the project. My website, “Researching Benjamin Researching: The Arcades Project Through the Eyes of a Digital Flâneur” creates a “montage effect” by allowing multiple ways of accessing and navigating this collection. Users can choose between the visual grid display, tags, categories (Material Artifacts, Catalogs, Images, Organizational Dialectics, Digital Translation, and Notes & Quotes), and a site table of contents2 as means of exploring facsimiles from Benjamin’s notebook alongside quotations from Benjamin’s project in an essay that bridging my analysis of his technique with work in digital humanities methodology and new media theory. The project intended to draw out the relationship between Benjamin’s theory of dialectical images and his information management systems.

Among the many informational devices at play in the project, one element struck me in particular: Benjamin’s use of an informational system that both captured the fluidity and nonlinear spirit echoed in the politics of dialectics and also served as the backbone of a burgeoning bureaucratic system of control and standardization: the index card and the card-catalog.

This chapter takes the Benjaminian index-card aesthetics as its jumping off point. Through the vehicle of the index-card as an analog for Benjamin’s system for information organization and retreival, I explore some of the critical tensions in The Arcades Project: the complex interplay between Benjamin’s writing––which engages with the cultural idea of information, ordering structures, and historical data––and the forms and systems that he uses to write them in. I engage with what is stake in reading the indexical imagination of The Arcades Project in and out of context. Arguing against a tradition of reading Benjamin’s project ahistorically I attempt to read the Arcades Project not as an early for of digital aesthetics, but, instead, as set of information-gathering and organizing practices informed by the aesthetics and logics of a set of documentary practices particular to the period of time which Benjamin was writing––1927-1940––and his engagement with a changing discourse surrounding the standardization of information and knowledge organization.

Reading The Arcades Project

As a massive document occupying a nebulous genre of history, historiography, poetry, Benjamin’s The Arcades Project presents a particularly thorny issue for scholars. Its documentary aesthetic has attracted attention to the form of the project for its literary sensibilities, its role as a philosophical treatise, or its status as an exercise in or critique of historiography. Through there is a breadth of work on Benjamin’s style and form, few have attempted to situate the project’s negotiation of knowledge within its historical moment; critics tend to focus on Benjamin’s nostalgia for nineteenth century bourgeois collecting practices, and the project’s nascent digital impulses. Both of these strands dehistoricize the project, or locate it only within a history of literary form or style.

In scholarship that reads the project through the lens of the nineteenth practices, there has been a particular emphasis on the material archiving and collecting practices at play in Benjamin’s work. Buck-Morss’s now-canonical reading of The Arcades Project expands on Benjamin’s material practices and the “layers of historical data” that constitute it. 3 Other scholars have tackled the importance of the archive for Benjamin as both the location and object of study,4 the dynamic political character behind Benjamin’s collected objects, 5 or the role of collecting as an articulation of the subjectivity of the collector.6 Many of these works focus on Benjamin as a collector, noting the ways in which bourgeois collecting practices pervade his work in the Arcades Project and elsewhere. Others attempt to read the project as an archive. In a recent exhibition on Walter Benjamin’s manuscripts and personal archive, the accompanying monograph describes the ways in which the Arcades Project functioned as a kind of metonymic archive of the whole, a mimetic replication of Benjamin’s larger collecting practices.7

In scholarship reading Benjamin vis-à-vis new media and digital aesthetics, media theorists have hailed the collection a precursor to hypertext. Critics read “the multiple entry points and nonlinear associational jumps across the material” as suggesting the “architecture of hypertext and multimedia” [^Featherstone910] and as a “ur-history of media space” 8. Others, like Rotstein and Schwartz suggest that his notion of aura looks forward to “database aesthetics” 9, or that his conception of the book as catalog anticipated hypermedia. 10 The Arcades comes to be described as a “ur-hyptext,”11 a “proto-hypertextual work,”12 and an “analog database.” 13 As Anca Pusca writes, the works seems to anticipate to the ways we imaging navigate and access information through digital and new media technologies. She suggests that the project’s affinities with the digital would make it an ideal form for displaying Benjamin’s text:

Internet technology and the ability to collect, categorize and re-arrange Benjamin’s fragments in an electronic publication form could perhaps provide Benjamin with a posthumous solution to his struggle to organize the Arcades Project in a manner that would both appease publishers and maintain its innovative framework. One can already imagine the possibilities of a new interactive electronic Arcades Project in which Benjamin’s fragments could easily be navigated through the click of a button, the text appearing as a digital image, a material fragment much closer to Benjamin’s original intentionality. 14

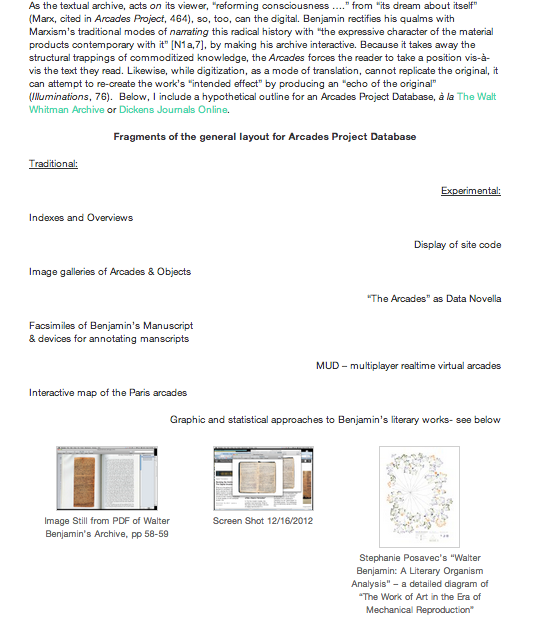

In my own site, I engage with some of Pusca’s suggestions for using new media to enhance the study of Benjamin’s work. On one page, I describe potential ways in which the digital form brings out new ways of navigating and manipulating information that Benjamin describes, sketching out a “Fragments of a general layout” for an “Arcades Project Database”:

In addition to the formal ways in which new media and digital technologies offer one avenue for imagining or conceptualizing Benjamin’s project, new media theory also offers a vocabulary for describing these structures, which can prove useful in discussing things like the networked or referential nature of Benjamin’s project.

Yet, reading information management tools as only pre-cursors that pre-suppose some yet-to-come, new (inevitably digital) media object erroneously collapses all engagements with informational management into the realm of the digital or the proto-digital, leaving no space for a critique of an alternative history. As Samuel Richardson’s The History of Sir Charles Grandison and Charles Reade’s Hard Cash show, clearly nonlinear reading an expressive or creative articulation, readerly affect, etc––happens at multiple points in history and is not unique to either Modernist innovation or digital media. Too much focus on how Benjamin might be positioned in a linear, progressive genealogy of experimental modes of reading causes both the material artifacts of Benjamin’s work and his own historical moment to disappear from the analytic frame. Galvanized by Anna Munster’s injunction not to read all information aesthetics as a pre-history of the digital,15 I propose an alternate reading, one that takes Benjamin’s project not a response to 19th century practice or an anticipation of 21st, but, instead focuses on how Benjamin’s information management devices are inextricably tied to changing emphasis in the forms of knowledge management during the early twentieth century rise of documentation.

The Structure of Reference in The Arcades Project

To say that reference and citation play an important role in Arcades Project would be a supreme understatement. Quotation, citation, and reference make up the bulk of the text of the project. Adding to the sheer volume of references, Benjamin includes a mechanism for classifying them. As Buck-Morss points out, Benjamin’s “keyword” system for labeling his convolutes come into the body of the entries in the form of cross-references as well. In my web-essay, I illustrate this phenomenon on one page of “Researching Benjamin Researching,” where draw on Benjamin’s use of visual tools in his system of cross-reference.

One possible framework for reading this massive web of references and the practice through which the text of the Arcades Project refers to them is that of “hypertext.” Hypertext, first theorized by Ted Nelson in the 1960’s, has come to be read into the non-sequential or non-linear tendencies of other texts. Nelson describes hypertext as:

non-sequential writing, […] the most obvious being that which simply connects chunks of text by alternative choices–we may call these links […]–presented to the user. 16

Hypertext theorist George Landow observes what he sees as a hypertextual inclination in Foucault’s The Archeology of Knowledge, where Foucault writes, the “frontiers of a book are never clear-cut,” because “it is caught up in a system of references to other books, other texts, other sentences: it is a node within a network . . . [a] network of references.” 17 Hypertext gives us a way of reading the practice of referencing and citing as not just a token means of presenting research evidence, but as a reading protocol that can engage, disrupt, and manipulate the attention of the reader in creating “passageways” between texts.

The temptation to read the interplay between passages/pathways and passages as hypertextual links in the Arcades Project is strong. Later in my web-essay, I make more direct claims to the ways in which this text functions as a hypertext, focusing on the critical fascination and my own approach to the citational and “rhizomatic” aspects of the project.

In her hypertextual compendium to the Arcades, Heather Marcelle Crickenberger takes a mimetic approach. She builds a hypertextual website mimicking the structure of the project:

In order to create the option of reading the site as a scholarly project, however, I decided to base my navigation system on that which Eiland and McLaughlin devised to house The Arcades Project […] I transposed Eiland and McLaughlin’s chapter headings into web-relevant equivalents. “About” replaced “Translator’s Forward” and will house this introductory essay as well as several others that address different aspects of this project’s production. I replaced “Exposés” and “First Sketches” with articles” 18

Crickenberger conjectures that “[w]ithout the primitive hyperlinks, the divagations imbedded in the text’s composition are not visually dramatized for readers as Benjamin had originally intended, although optic apparatuses of divagation and diversion are a primary obsession.” 19

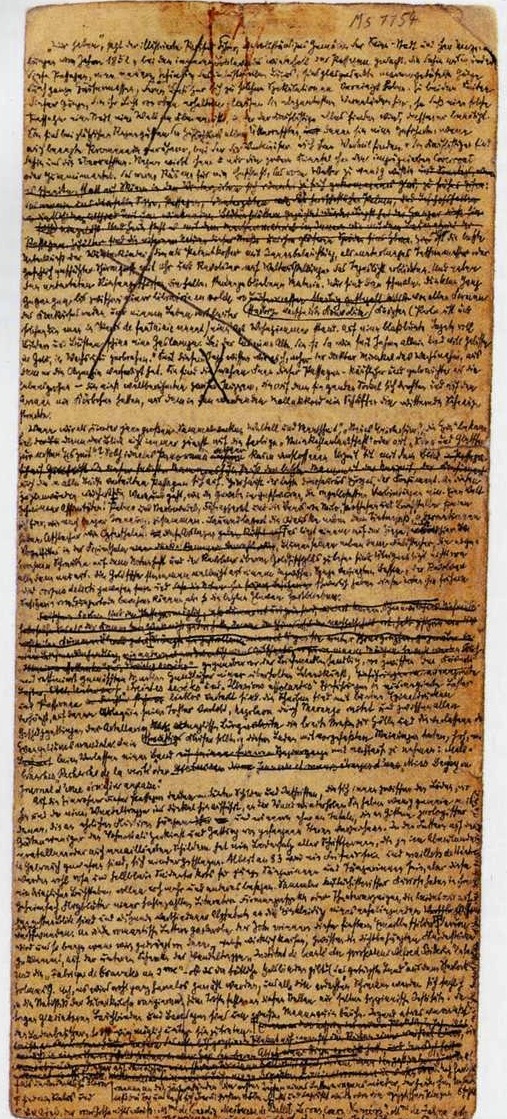

While hypertext does provide a vocabulary and a framework for discussing the structure of reference in The Arcades Project, it is not a perfect analog for the structure of Benjamin’s work. For one, rather than “lateral, non-hierarchal links between arbitrary nodes,” 20 Benjamin’s text follows a particular order in the placement of entries in the text, and thus, in the structure of the references between the entries.  Instead of placing individual entries on their own pages––which would evoke more of the feel of hypertext––Benjamin lists them sequentially within the notebooks, as in the facsimile to the right, and, as Ursula Marx notes, when Benjamin recopied the manuscripts, he retained this order, indicating a methodology behind the specific arrangement of entries. This isn’t to say that The Arcades Project does not imagine a reader-flâneur who wanders through the text skipping and skimming––it most certainly does––but rather, that this process of hyper-reading occurs against the backdrop of a printed, not digital text, one that is consciously working with the specifically materiality of that form in rigidity of the printed page and in the visual experience of a information.

Instead of placing individual entries on their own pages––which would evoke more of the feel of hypertext––Benjamin lists them sequentially within the notebooks, as in the facsimile to the right, and, as Ursula Marx notes, when Benjamin recopied the manuscripts, he retained this order, indicating a methodology behind the specific arrangement of entries. This isn’t to say that The Arcades Project does not imagine a reader-flâneur who wanders through the text skipping and skimming––it most certainly does––but rather, that this process of hyper-reading occurs against the backdrop of a printed, not digital text, one that is consciously working with the specifically materiality of that form in rigidity of the printed page and in the visual experience of a information.

Where hyptertext is perhaps most useful is in finessing the particular form of Benjamin’s practice of referential pointing. Taking each one of Benjamin’s references as a node, and tracing it to its corresponding endpoint, we see that, with Benjamin’s frequent use of cross reference and his tendency to omit bibliographic information from entries, the links lead the reader between entries, not back to the original source texts. Benjamin’s system of cross reference is more of a taxonomic system than a one-to-one relation between pieces of text. Within this system, the spatial placement, rather than the specificity of references, becomes important Even Benjamin’s disorder can be seen protocol for collecting and control in the Arcades has everything to do with arrangement. Take, for example, a selection from Konvoute H: The Collector:

The ancestors of Blathazar Claës were collectors

Models for Cousin Pons: Sommerard, Sauvageot, Jacaze

The physiological side of collecting is important… 21

None of these quotations include bibliographic references, nor do they include Benjamin’s cross-references. Taken out of context, as an individual entry, none of these would necessarily link to the others. Here, the position of the information on the page is what creates relationships and links between these three discrete pieces of information. Rather than linking hypertextually in a one-to-one correspondence between two pieces of text, the connections between individual entries in this section and elsewhere in the project, function more as a kind of assemblage or collection.

Hypertext provides a vocabulary for describing the intricate structure of reference and cross reference in the text, and the ways it allows for a disrupted, fractal-like path through the text. Benjamin’s quotations are hypertextual only insofar as they allow for non-linear reading; yet they do not create one-to-one relationships between pieces of information. The structure of reference, rather than being intertextual, is intratextual––existing between entries and groups of entries and, given the relative sparseness of bibliographic information, staying within the interior spaces of the collected fragments in the project.

The Arcades Project and the European Documentation Movement

Benjamin’s collecting practice and his use of reference in his desire to “write books like catalogues” seems to suggest an anti-systematic system, one that turns documentation itself on its head. Yet this practice takes an odd twist when we consider this seemingly experimental, radically skeptical mode of historiography alongside its historical context, “European documentation movement,”22 which was the epitome of institutionalized documentary practice and which, most interestingly, and whose proponents expressed a similar vision for the “book as catalogue.”

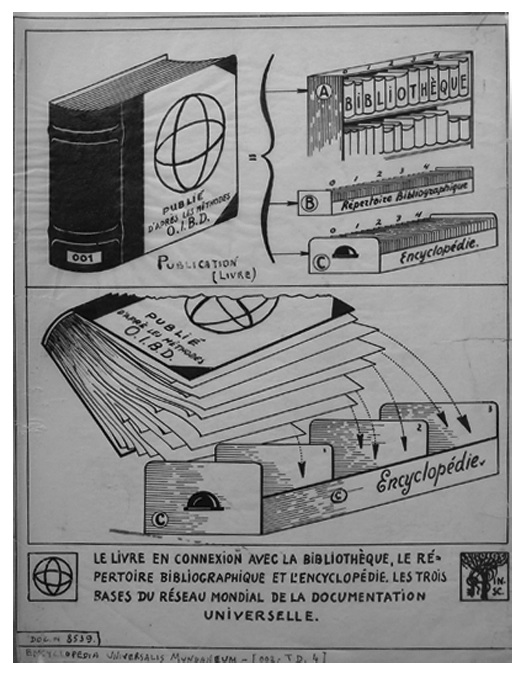

Spanning from the 1890s to the 1930s in Europe, the movement was led by practitioners in libraries, archives, and the field that would later be known as information science. Belgian Paul Otlet was a forerunner in the movement, publishing some of its key texts, Traité de documentation (1934) and Monde (1935)––and founding the International Federation of Documentation (FID). Otlet envisioned a kind of “universal system” for the organization of documents, one that quantified the world in terms of four variables: “facts, interpretation of facts, statistics, sources. All of its materials are reducible to these four terms.” 23 For Otlet,

The external make-up of a book, its format and the personality of its author are unimportant provided that its substance, its sources of information and its conclusions are preserved and can be made an integral part of the organization of knowledge, an impersonal work created by the efforts of all.24

Otlet believed that this slicing up of the book or written text into discrete bits of information that were then labeled and classified for efficient retrieval would allow for “the creation of a kind of artificial brain by means of cards containing actual information or simply notes of references.”25 one that he later refers to as the “Repertory” or “monographic principle.”26 Influenced by the work of Patrick Geddes, who proposes an “Index Museum,” Otlet’s vision includes an indexical “International Museum,” an instrument that assisted the visitor in learning how to see things universally and that took the indexing principle as a model for universal knowledge.27

Perhaps more influential on Benjamin’s engagement with information systems was the discourse of “documentalism” in France, championed by Suzanne Briet, librarian and head of the reference room in the Bibliothéque Nationale from 1924 to 195428. Documentalism described information management as a kind of cultural practice that imagined the organization and management of a vast network of documents. In her 1951 essay, “What is Documentation?” Briet defines the “document” as an “indexical sign.” To illustrate this point, she famously describes the process by which a hypothetical new species of antelope enters the realm of public knowledge. In a process of “documentary fertility,” the antelope enters the sphere of public knowledge “weighted down under a ‘vestment of documents’”: it is cataloged, recorded, and these documents might be recopied, selected, analyzed, described, translate, and then finally, the documents themselves might be classified.29 In Pericean fashion, a material chain of documents is formed all pointing back to the “originary fact” ––in this case, the existence of a new species of antelope. The documentalists were a forming group of professionals whose job it was to preserve and make usable this documentary excess. This form of documentation, according to Briet, is a “cultural technique”30 and a material one: “‘Homo documentator’ is born out of new conditions of research and technology [technique].”31

Both Otlet’s “artificial brain” and Briet’s network of “indexical signs” arise out of two important material infrastructures. First, the documentalists establish standardized and mobile forms of information management devices, including as the portable card catalogs of index cards32 paired with systematic labeling conventions. Second, the documentalists standardize the social process of documentation as well, through the establishment of institutional loci for documentation. Briet describes the rise of documentation centers in France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland,33 and in 1937, Otlet and Henri LaFountaine’s International Institute for Bibliography (founded 1895) becomes the International Federation of Documentation (FID).34

The European Documentation Movement was not just an abstract current of intellectual thought; it actually manifested materially in the place where Benjamin was working. Ronald Day notes in his account of the movement that Briet was the head librarian of the reference room in the Bibliothéque Nationale––and that during those year, Benjamin would have been quite familiar with the space, having conducted much of his archival research there. Briet also worked alongside the man that Benjamin would later entrust with the manuscript of The Arcades Project––librarian and literary critic Georges Bataille.35

Though Day observes this connection, he quickly moves on to address Benjamin’s philosophical conceptions of information and the ways materialist historiography serves as a critique of “the social machinery whereby ‘information’ was produced and reified,”36 and abandons the image of Benjamin the researcher in the “documentalist” library. Yet it seems curious that he does not dwell on the material connections between Benjamin’s research practices and the changes in ideas and material practices surrounding documentation and the way information is organized, recorded, and conceptualized. While Day astutely observes that Benjamin’s position as a historical materialist challenges a notion of information that takes its “reified value as empirical fact,” 37 this point can and should be complicated by Benjamin’s own documentary and informational practices. In fact, it is Benjamin’s status as a historical materialist serves as an invitation to look more at the material methods through which Benjamin’s own knowledge products were constructed.

Returning to the documentalists, the similarity between their documentary practices and Benjamin’s historiographical practices provides a striking historical precedent for the structure and form of The Arcades Project. Otlet’s monographic principle imagines the book as a “structure of cards”(illustrated) 38 or catalog, while Briet’s emphasis on the cultural and historical role of documentation bears an eerie similarity to Benjamin’s “books like a catalogues.” The intellectuals in this movement, like Benjamin, imagined the role of the material information device plays in forming social consciousness.

OTLET’S SYSTEM OF UNIVERSAL DOCUMENTATION

In their protocol, the documentalists emphasize the ways that forms of knowledge are acutely dependent on the forms of knowledge management. Briet describes as “a powerful means for the collectivization of knowledge and ideas” through documentation’s twofold process of “always increasing abstract and algebraic schematization of documentary elements (catalogs, codes, classifications) and the creation of “a massive extension of ‘substitutes for lived experience’” through secondary records. 39 The attention to the material devices of information management – the catalog, the index card, the list––in European Documentation movement suggests the need for a closer examination of Benjamin’s own elaborate indexical devices and the role they are seen as having in memory and information retrieval of culture.

Benjamin’s Information Aesthetics: The Romance of the Fragment/Archive

Examining the forms of knowledge in The Arcades Project means examining the presentation of information in its material form. This, in turn, requires an investigation Benjamin’s two aesthetic paradigms for organizing and managing the text as information: the logic of the fragment and the logic of the infinite archive.

The Arcades Project takes around the idea of small, information-packed fragments as one central organizing principle. Benjamin describes his the principle of montage: “to assemble large-scale constructions out of the smallest and most precisely cut components. Indeed, to discover in the analysis of the small individual moment the crystal of the total event.” 40 Here, these “small individual moments” as echoing the kind of notion of the fragment that, in its discreet autonomous structure, resemble the “moselization” that happens in co-creation of information as bit and system.41 For Nunberg, and for Benjamin, this conception of information relies on the semantic meaning, rather than meaninglessness of the small bit of information. The emergence of what Benjamin calls the “total event” from these small and precisely cut “crystals” illustrates a conception of the “granularity” or “level of descriptive detail in a record created to represent a document or information resource,”42 that contributes to the richness of these small individual moments.

On the other end of the spectrum is the logic of the “large-scale construction.” The act of collecting information in a repository provides an occasion for the imagined mastery of this “total event.” The experience of The Arcades Project relies tremendously on the power of scale at different registers. The small fragments gain significance in the many possible permutations for reading patterns: they can be read in juxtapositions with neighboring entries, with other entries with each the Konvolute, and within other entries in the project writ-large. Given the size of the project, it becomes possible for the reader/viewer/user of the Arcades Project to become lost in the expansiveness of the text. Describing his encounters with the project as a kind of pleasurable serendipity, Kenneth Goldsmith writes:

opening a chapter at random, you stumble upon a quote from Marx about price tags and commodities, then, a few pages later, there’s a description of a hashish vision in a casino; jump two pages ahead and you’re confronted with Blanqui’s quote, ‘A rich death is a closed abuse’.43

As Goldsmith articulates, with a not-too-subtle tinge of what resembles “archive fever”––the reader experiences knowledge in a vast and seemingly infinite scale in this project.

At stake in the aesthetics of information in the project are the ways in which the reader reads, and conceptualizes knowledge through the experience of different scales of information. Benjamin presents the Romantic unattainable, absolute horizon of “totality” in both the fragment and in the vast, unmappable assemblage as a whole. On one level, the project performs a classically Modernist move––resisting a single grand narrative through a multiplicity of possible narratives, a deferral which nonetheless maintains the utopic possibility of such a narrative. Yet it does so through the lens of information. This epistemological problem is experienced through the text itself and at the level of design; Benjamin’s use of labels for each of his entries help contribute to the sense of small, discreet units of information, while the vast and heterogeneous––ranging in length, language and degree of authorial commentary––collections of quotes he includes contribute to the sense of the infinite at the level of the large scale construction. By introducing disorder and deferring totality (though not totalizing structures), Benjamin’s information aesthetics ––made eminently more visible by Benjamin’s playful, poetic, and gnomic construction of the project––force the reader to confront their own expectations about the way knowledge is consumed.

“The Card Index”: The Material Form of The Arcades Project

Numerous material forms appear in the pages of the Arcades Project, ranging from catalogs, to lists, to tables of contents. Of all the myriad information technologies, the index card was arguably the most distinctively twenty-first century one. Attending to the role of the index card in producing and shaping the project reveals the ways in which the mobility and flexibility of this particular kind of indexicality ––the index card––shapes the structure of knowledge in The Arcades Project.

Benjamin would have had ample exposure to the card index as a research technology in the reading room of the Bibliotheque Nationale, as I note in “Researching Benjamin Researching,” and the influence of the card catalog can be seen at the level of the structure of the project. Benjamin even writes directly about his encounters with “card index” or “card catalog.” In separately published essays, he muses on that these particular form of information management changing the way in which scholars write:

The card index marks the conquest of three-dimensional writing, and so presents an astonishing counterpoint to the three-dimensionality of script in its original form as rune or knot notation. (And today the book is already, as the present mode of scholarly production demonstrates, an outdated mediation between two different filing systems. For everything that matters is to be found in the card box of the researcher who wrote it, and the scholar studying it assimilates it into his own card index.)44

Later, in One-Way Street, Benjamin expands on this notion of “three-dimensional writing” as the future of scholarship. In a brief essay entitled a “Teaching Aid: Principles of the Weighty Tome, or How to Write Fat Books,” Benjamin follows a humorous list of principles for accumulating an “abundance of examples” with a more serious observation:

The typical work of modern scholarship is intended to be read like a catalogue. But when shall we actually write books like catalogues? If the deficient content were thus to determine the outward form, an excellent piece of writing would result, in which the value of opinions would be marked without their being thereby put on sale.45

The Arcades Project stands as the obvious answer to the question of how to “write books like catalogues.” Benjamin’s own work navigates the problem of the catalog, index and archive––questioning what constitutes an archive in his insistent memorialization of all manner of objects. Though never compiled into a codex during Benjamin’s time, the fact that Benjamin wrote his index card-esque entries on full manuscript pages (rather than index cards) forces the reader to recognize the tensions in literal “mediation between two filing systems” in a text that brings together the two filing systems of the card catalog and the codex.

This index logic appears in the systematic use of discrete portions of information enumerated by subject keyword. Individual entries in the project are labeled and number according to subject keyword, and then filed in the appropriate konvolute, like a more rigid keyword card catalog, a process of keywording and filing present from the early days of the project. Benjamin’s preliminary “first sketches” of the project show how even his research queries are enumerated, ordered, and filed as separate entries in this writing system:

Query for the arcades project.

Does plush first appear under Louis Philippe?

<E, 45>

What is a “drawer play”? (Gutzkow, Brief aus Paris, vol. 1, p. 84––(pièce à tiroirs?)

<E, 46>

At what tempo did changes in fashion take place in earlier times?

<E, 47>

Find out the meaning of bec de gaz in argot and where it comes from.

<E, 48>

Read up on the manufacture of mirrors <E, 49>

This continues for the rest of section E, <E, 45> through <E, 59>, and continues throughout the first sketches in the other Konvolutes. The significance of the cataloging labels can be seen in the ways in which these notes evolve: <E, 49> becomes in an entire six page Konvolute R, while others, like <L, 23> becomes <C2,4>.46

While it might seem crudely materialist, the simple issue of page navigation and the changing of card label here illustrates the relationship between the information management apparatus Benjamin and the kinds of formal ways it play into his historical and philosophical thought. By collating the entries on linear sheets of paper, the Arcades Project perhaps disrupts the convention of reading the card as individual entries by suggesting the possibility of reading them in a connective path; at the same time, it also disrupts a convention of linear reading by segmented the text into index card-esque entries that seem to insist on the own singularity even when collated together. The effect of this “mediation” is not so much the pitting of narrative against information––a distinction troubled that all of the texts I examine, from Benjamin to Lenat to Reade to Richardson, in some way trouble––but the revelation of the interconnections between information management and reading. The logic of the index here shows how linear reading is itself a filing and information management system. Out of the indexing and filing systems used to manage knowledge in the The Arcades Project emerge two alternate possibilities for epistemological frameworks: one in which knowledge emerges organically in the autonomous self-assembly of facts and one in which the knowledge and its forms are the direct product of selective curation on the part of the collector .

The Politics of Benjamin’s Index-Cards

The affinities between Benjamin’s Arcades Project and its historical context–– the European Documentation Movement––despite their seeming philosophical disparities, brings the question of ideology of information retrieval to the forefront. The role of the index card in shaping thought is not a new concept. Kittler notes that Hegel, in the Phenomenology of Spirit, described the spirit as “a hidden box of index cards.”47 Day describes the European Documentation movement as unabashedly “scientific” in the utopic vision of systems and technologies for universal knowledge. Briet and Otlet were both devoted to the notion “scientific” documentation.”48

Like Benjamin, documentalist Suzanne Briet saw the centrality of the centrality of index cards and card catalogs in the new modes scholarly production in early decades of the twentieth century. She describes how index cards arise out of a need to file and sort increasing quantities of documents in the practice of systematic, institutionalized documentation:

These notes have to be extremely mobile, able to be classified according to the needs of a desired order, and to be interfiled without delay in series that are instantly extensible. These needs lie at the origin of the invention of the card. 32

What’s key in Briet’s definition is the “extreme mobility” of the index card as a form of knowledge storage that can be interfiled and re-shuffled. Unlike a manuscript index, the index card (and the card catalog it sits in) offer a distinctly mobile kind of index, where discrete parts of the card catalog could be shuffled, re-ordered, in a manner that was “instantly extensible.” Briet’s emphasis on mobility and combinatory possibility resonates as familiar. Benjamin’s efforts to depict dialectical images “at a flash” in a constantly growing and never-completed project seem to take up and capitalize on this combinatory and recombinatory function of the index card––its status as an ordered object that might be re-ordered.

In Briet’s second function of the index card, the political implications of its modularity fully manifest. In addition to an emphasis on mobility, this form of standardized knowledge organization hinges on modularity:

Statistical data-processing gets us accustomed to replicating the cards that are legible with cards in which each mark is a conventionally agreed upon translation for the directly intelligible signs.49

This logic of equivalence rests on the fact that index cards can represent different but equivalent data (and thus allowing for a sorting, filing, and file retrieval system). Markus Krajewski draws a parallel between these circulable slips of paper and the logic of paper money.50 Here, this logic of systematization is a familiar one in studies of information science ––this is the twentieth century emphasis on “systematic” information management that is continuously and anachronistically read back onto eighteenth and nineteenth century information management systems––can be localized not as a specific product of the index, but a formal shift that we can see materially play out in the shape of the index card.

Walter Benjamin’s position seems to put him starkly opposed to this systemic mode of information management, yet his information management techniques tell a different story. He bemoans in the opening of the first exposé the way nineteenth century newspapers present “a viewpoint according to which the course of the world is an endless series of facts congealed into the form of things.” 51 The simple fact that the Arcades Project also uses on relies on and uses the logic and aesthetics of the index card pervasively throughout the project, which calls into question the degree to which the philosophical imperative of the project can be separated from the politics of its forma and aesthetics. In an early sketch for the Arcades, Benjamin describes his process of composition as a “formula” for gathering texts:

Formula: construction out of facts. Construction with the complete elimination of theory. <O?, 73>

This line, which later becomes his famous “Method of this project: literary montage. I needn’t say anything. Merely show” quotation, encapsulates the tension embodied in the politics of the index-card as a formula of information management. While this description of writing as a “construction out of facts” might recall Charles Reade’s “matter-of-fact romance”, Benjamin’s “formula” here calls attention to a kind of latent objectivism existing in the utopic aspirations of the project. Others have pointed this positivistic trend in the project. Holdengraber notes that “collecting is the master-trope of Benjamin’s work”52 and Benjamin’s friend and fellow critical theorist, T.W. Adorno, remarked in a letter to Benjamin that the text’s “wide-eyed presentation of mere facts” bordered on “positivism.”53 Adorno’s skepticism of the project’s faith in not just the principle of “construction out of facts” but the material structures that might allow a vast construction out of facts to, in Benjamin’s own words elide “theory” and, we might read, by extension, “ideology.”

Form and content are inexorably linked, and this ideological component to the politics of Benjamin’s indexical entries extends to what is indexed as well as how it is indexed. Benjamin’s own skepticism of the universal truths of historicism invites a reading that takes a skeptical eye towards the “facts” that are being incarnated as catalysts for the emergence of dialectics in this system. The universalist utopia of knowledge imagined by the documentalists also echoes in Benjamin, who, despite attempting to depict the remnants and remainders overlooked by history, also contains collects and indexes a highly selective segment of 19th century Parisian culture: Benjamin’s sources are, unsurprisingly predominantly white and male. Women authors are almost never quote, women figure in collection as prostitutes, objects, and shoppers, with only a handful of citations of female authors.

One way of bridging, if not reconciling, Benjamin’s faith in the kind of autopoetic structures for constructing out of facts here, and his critique of objective historicisim’s collective truth is by focusing on the use of the index-card as a practice. Jeremy Braddock observes that a “collecting aesthetic” appears as contingent structures in modernist art. In this set of protocols, collectors, curators, and assemblers during the early twentieth century operate at a slant to formal institutions (like those of formal documentation centers), but who nonetheless use and manipulate the structures of control afforded by this information management system and its centralizing force in forging a kind of “provisional institutionalism.”54 In this sense, we might read Benjamin’s provisional indexing as not just a signifier of collecting, (like a “research effect”), but as a material strategy for situating and negotiating the Arcades Project vis-à-vis more institutionalized, or legitimate structures and centers for knowledge. Even as an intervention in the material order of knowledge, Benjamin’s project nonetheless engages with the same material structures and the utopic ideal afforded by them.

Authorial Indexicality: Benjamin as the Collector and Indexical Interiority

There are multiple ways of reading the aesthetics in Benjamin’s practice of indexing and collecting: as both a totalizing aesthetic and one that defers totality, and as a structure of referencing and curating in order to make historical artifacts “present.” Read through a more ideologically-suspicious lens, The Arcades Project also displays a particular kind of indexicality, that I call “authorial indexicality,” where the things that it “points to,” are its own interiors and the subjectivity of its author.

For Benjamin, the subjective dimensions to a collection are preserved through their indexical links to the collector. In his essay on the collector, Benjamin observes how,

the phenomenon of collecting loses its meaning when it loses its subject [the individual collector]. Even though public collections may be less objectionable socially and more useful academically than private collections, the objects get their due only in the latter.55

The important link here between the collection and the collector is the manner in which the traces of the collector are thus indexed in their collected objects. The modernist collection, Jeremy Braddock notes, functions not entirely in opposition to the totalizing social institutions frequently depicted as the opposite of such “assemblages,” but as a kind of provision institution with their own socializing ambitions. Reading the particular order of the Barnes collection alongside Barnes’ theories on the psychology of art, Braddock argues that models both aesthetic gaze and new social practices through the curatorial practices of the private collection.56 In a similar vein, this indexing of the collector and the collecting practices serve to implement a specific mode of seeing (the “dialectics of seeing” that Buck-Morss notes in Benjamin’s project) and that this kind of documentation emerges alongside and al a partial appropriation of the institutions of collecting (the documentation centers, information bureaus, and libraries).

Benjamin’s collector at once emerges as both the primary “orderer” and the primary individual experiencing the order of their collected objects.57 At the same time, these impressions give rise to a sense of what Braddock describes as Benjamin’s obsession with the hero-figure of the collector.58 The collector is the one who “brings together what belongs together; by keeping in mind their affinities and their succession in time, he can eventually furnish information about his objects.”59 This information is eventually presented in a form that communicates the collector’s own aesthetic paradigms and modes of seeing. The materials collected, assembled, ordered, and stored in the Arcades Project index the memory of their collector, serving as indicators of what Benjamin-as-collector saw and wished to remember about nineteenth century Paris.

Benjamin’s theories on collecting are worth examining in detail here, not as a key to reading his own collecting practices, but for a glimpse of the collector-figure that emerges in the Arcades Project and other texts. The collector’s reification of the collected object relies on a logic of fetishization similar to that of the commodity, but rather than speaking of abstracted exchange value, the information communicated by the collected object is that of the collector. Though Benjamin argues that the removal of the collected object from the exchange market is what sets it apart from the commodity and its economy, the collector’s “possession” of the collection and its object, the notion of privatization that collecting, is at once oriented towards documenting and making present for the viewer. In focusing on the collector’s possession of the collected objects, and their relation–spatially, semantically–to the collector, the Arcades creates a constellation structured around the collector’s collecting processes. These processes, in the Peircean sense of an index that traces a “force” (link to index section) through its influence on the object, reveal the process of privatization that occurs in collection. Jean Baudrillard note that this “structure of the system of possession” constellates the collector in the chain of signifiers that point, “a given collection is made up of a succession of terms, but the final term must always be the person of the collector.”60

Like the modernist anthologies and visual art collections, the structure of reference Arcades Project, even in its notes form, as evidenced by the attention to layout, indicates a use of the order of these individual entries to achieve a particular effect. We can see how Benjamin’s attention to order and process of refining his system– in “First Sketches,” entries <E?, 24>, <E?, 25><E?, 26> became <Q1a,1>, <A3a,6>, <T1a,9>, respectively61– entails the movement and re-arrangement of entries, and how the Arcades uses links in a highly controlled fashion, drawing on both the logic of information in structuring individual entries and manipulating some of the conditions under which they are read and experienced. The curatorial selection behind the layout of the Arcades project determines the structure of reference. Especially in a collection so acutely aware of the problems of epistemology, historiography, and the forms of knowledge, it would be naive to overlook the role of interpretative selection in of managing the indexes of the project. To take it one step further, the emphasis Benjamin places on removing the “use-value” of information in order to place it firmly in the space of the collection suggests Benjamin’s effort to redirect meaning of the collected object from the realm of instrumental use back to the work of tracing or making present the collector. The aesthetic choices determined at each point by the collector illustrate indexing as both a “practice of collecting” and a method of composing

Documentation and Generative Interfaces

In the eyes of Benjamin and Briet, the space of the index-card is a productive and generative space. Though the process of index-card-style indexing allows it to serve as a tool for systematization and control, the index, as a form, is never merely purely systematic, and neither is the index-card. The Arcades Project draws out two of the most generative and productive elements aspect of the index-card: its capacity for serendipitous creation and its potential as a tool for making objects present in memory.

Writing about the rise of index cards in Germany during the early twentieth century, Krajewski notes their often under-appreciated capacity for serendipity:

Every note in an index can refer precisely to another […] With the aid of these connections the user succeeds in tracking down new connections following the reference structure of entries, uncovering unintended readings. ‘The box of index cards yields combinatory possibilities that have never been planned, anticipated, or conceived in this way.’62

This notion of an instrumental device as give rise to something surprising recasts the index card as a tool for both systematic mapping of the known and for playful discovery of the unknown. In fact, this quality comes as part and parcel to the index-card’s function in the imagining of large, systems of reference: this kind of combinatory play requires the links an connections between indexed objects in order to function and is only possible once enough information has been accumulated.

Benjamin builds off this idea of “completeness” in Konvolute H, his convolute devoted to “the collector”:

What is decisive in collecting is that the object is detached from all its original functions in order to enter into the closest conceivable relation to things of the same kind. This relation is the diametric opposite of any utility, and falls into the peculiar category of completeness. What is this “completeness”? It is a grand attempt to overcome the wholly irrational character of the object’s mere presence at hand through its integration into a new, expressly devised historical system: the collection. And for the true collector, every single thing in this system becomes an encyclopedia of all knowledge of the epoch, the landscape, the industry, and the owner from which it comes.”63

In this new “historical system,” part of the power of the card index as an organizing form is this utopic ideal of infinite connectivity as a means for sparking new knowledge through association. For Benjamin, the process of bringing the object, the piece of information into the collection places it into new relations with new similar objects, but it also severs the object “from all its original function” removing it from a physical and existential link back to its origin. In this process, knowledge forms in the wake of new dialectical relations, building what Benjamin will later call a “magical encyclopedia.”

The second component to Benjamin’s collecting and indexing practice is the role of documentation in the phenomenological experience of “presence.” To ground his allegoric description of collection in the work of the Arcades Project, the presence of a quotation or citation in the pages of the work brings the object into the collection not through a process of mimesis, but through a process of pointing and referring. Benjamin’s own careful attention to the phenomenology of collected objects and their “mere presence.” He later, like Peirce, uses the allegory of the photograph to describe this process of reference and the temporal, embodied experience as and effort “to represent them [the collected objects] in our space (not to represent ourselves in their space).”64

Neither Benjamin’s project nor the European Documentation movement (despite, perhaps, its intent) present a uniform articulation of the form of knowledge produced by these indexical devices. In addition to describing its possibilities for systematization and efficiency, Briet stresses the generative dimensions to documentation:

Documentation, while it is intimately tied to the life of a time of workers or scientists or scholars––or while it participates in an industrial, commercial, administrative, teaching activity, etc., can in certain cases end in a genuine creation, through the juxtaposition, selection and the comparison of documents, and the production of auxiliary documents.” 65

Couched as it may be, Briet articulates a radical sentiment: the notion that indexical pointing or juxtaposition can serve as not just a way of marking, noting, labeling but also “genuine creation.” As Benjamin’s indexical project can and does veer into the realm of rigid totalities, the possibility of the card catalog or the “construction out of [indexed] facts” to lead to “genuine creation” remains the hopeful horizon of both Benjamin and Briet’s indexical imaginaries.

-

Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991), 67. ↩

-

The WordPress theme I chose and modified displays the posts visually in a fluid layout that can be rearranged and would change depending on the size of the viewer’s browser window, disrupting the linear passage through the selections of text I had written. ↩

-

Buck-Morss, ix. ↩

-

Sigrid Weigel, Body-and Image-Space Re-Reading Walter Benjamin (New York: Routledge,, 1996), 133, see also, Katherine Arens, “Stadtwollen: Benjamin’s ‘Arcades Project’ and the Problem of Method,” PMLA 122, no. 1 (January 1, 2007): 44. ↩

-

See John Plotz, “Out of Circulation: For and against Book Collecting,” Southwest Review 84, no. 4 (1999): 462–478, and Nicholas Thoburn, “Communist Objects and the Values of Printed Matter,” Social Text 28, no. 2 103 (June 20, 2010): 2. ↩

-

Joseph D. Lewandowski, “Unpacking: Walter Benjamin and His Library.” Libraries & Culture 34, no. 2 (April 1, 1999): 151–57. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, Walter Benjamin’s Archive: Images, Texts, Signs, ed. Ursula Marx et al., trans. Esther Leslie (Verso, 2007). ↩

-

Jaeho Kang, “The Ur-History of Media Space: Walter Benjamin and the Information Industry in Nineteenth-Century Paris,” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 22, no. 2 (June 1, 2009): 247. ↩

-

Aviva Yael Rotstein, “Re-Collections: Auratic Encounters with Database and Archival Artworks.” (Thesis, Communication, Art & Technology: School of Communication, 2013), http://summit.sfu.ca/item/12932. ↩

-

Vanessa R. Schwartz, “Walter Benjamin for Historians,” The American Historical Review 106, no5 (December 1, 2001): 1739 ↩

-

Marjorie Perloff, Unoriginal Genius: Poetry by Other Means in the New Century (Chicago; Bristol: University of Chicago Press?; University Presses Marketing, 2012), 31-32. ↩

-

Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 115. ↩

-

Paul Caplan, “London 2012: Distributed Imag(in)ings and exploiting Protocol,” Platform: Journal of Media and Communication 2, no. 2 (September 2010), 35. ↩

-

Anca Pusca, “On Benjamin’s Public (Oeuvre),” The Public Domain Review, October 31, 2011, http://publicdomainreview.org/2011/10/31/on-benjamin%E2%80%99s-public-oeuvre/. ↩

-

Anna Munster, Materializing New Media Embodiment in Information Aesthetics. (Hanover, N.H.: Dartmouth College Press: Published by University Press of New England, 2006). ↩

-

Theodor H. Nelson, Literary Machines (Mindful Press, 1993), 1.15. ↩

-

George P Landow, Hypertext: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992). ↩

-

Heather Marcelle Crickenberger, “The Arcades Project Project,” The Arcades Project Project, December 2007, http://www.thelemming.com/lemming/ dissertation-web/home/structure.html ↩

-

Howard Caygill, “Meno and the Internet: Between Memory and the Archive,” History of the Human Sciences 12, no. 2 (May 1, 1999): 8. ↩

-

Benjamin, Arcades Project 208. ↩

-

Michael Buckland, “On the cultural and intellectual context of European Documentation in the early twentieth century” published as Chapter 2, pp 44-57, in: European Modernism and the Information Society: Informing the Present, Understanding the Past, ed. W. Boyd Rayward. (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2007), 44. ↩

-

Paul Otlet, International Organisation and Dissemination of Knowledge: Selected Essays of Paul Otlet ed. and trans. byW.B. Rayward (Elsevier, 1990), 16. ↩

-

Otlet, 17. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Otlet, 149. ↩

-

Wouter Van Acker, “Internationalist Utopias of Visual Education: The Graphic and Scenographic Transformation of the Universal Encyclopaedia in the Work of Paul Otlet, Patrick Geddes, and Otto Neurath,” Perspectives on Science 19, no. 1 (2011): 32–80. ↩

-

Michael Buckland, “A Brief Biography of Suzanne Briet,” in What Is Documentation?: English Translation of the Classic French Text, trans. Ronald Day (Scarecrow Press, 2006), 1. ↩

-

Suzanne Briet, What Is Documentation?: English Translation of the Classic French Text, trans. Ronald Day (Scarecrow Press, 2006), 10-11. ↩

-

Briet, 13. ↩

-

Briet, 20. ↩

-

Suzanne Briet, What Is Documentation?: English Translation of the Classic French Text, trans. Ronald Day (Scarecrow Press, 2006), 27. ↩ ↩

-

Briet, 11. ↩

-

See Michael Buckland’s timeline “1895-200 FID Achievements” on http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~buckland/fidhist.html. ↩

-

Ronald E. Day, The Modern Invention of Information: Discourse, History, and Power (Southern Illinois University Press, 2001), 112-113. ↩

-

Day, 92. ↩

-

Ibid 109. ↩

-

Charles van den Heuval and WB Rayward, “Facing Interfaces: Paul Otlet’s Visualizations of Data Integration,” Journal Of The American Society For Information Science And Technology 62, no. 12 (2011): 2317. ↩

-

Briet, 31. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin and Rolf Tiedemann, The Arcades Project (Harvard University Press, 1999), N2,6. ↩

-

Jeffery Nunberg, The Future of the Book (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996). ↩

-

See “granularity” as defined in the Online Dictionary of Library and Information Science, http://www.abc-clio.com/ODLIS/odlis_g.aspx. ↩

-

Kenneth Goldsmith, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2011), 115. ↩

-

Walter Benjamin, Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings. Edited by E. F. N Jephcott and Demetz, (New York:Schoken: 2007), 78. ↩

-

Benjamin, 79. ↩

-

Benjamin, AP, 837. ↩

-

Krajewksi, 57. ↩

-

Ronald E. Day, The Modern Invention of Information?: Discourse, History, and Power (Southern Illinois University Press, 2001), 3. ↩

-

Briet, 29. ↩

-

Krajewski, 160. ↩

-

Benjamin, AP, 14. ↩

-

Paul Holdengräber, “Between the Profane and the Redemptive: The Collector as Possessor in Walter Benjamin’s ‘Passagen-Werk,’” History and Memory 4, no. 2 (October 1, 1992): 101. ↩

-

Letter from Adorno to Benjamin, November 1938. Theodor W. Adorno and Walter Benjamin, The Complete Correspondence, 1928-1940 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 291. ↩

-

Braddock, 3. ↩

-

Benjamin, Illuminations (New York: Schocken, 1969) 67. ↩

-

Braddock, 110. ↩

-

Ibid, 207. ↩

-

Jeremy Braddock, Collecting as Modernist Practice (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012). ↩

-

Benjamin, Arcades Project, 211. ↩

-

Jean Baudrillard, “The Systems of Collecting,” in The Cultures of Collecting, ed. John Elsner and Roger Cardinal (Harvard University Press, 1994), 12. ↩

-

Benjamin, Arcades Project, 836. ↩

-

Markus Krajewski,Paper Machines: About Cards & Catalogs, 1548-1929. Translated by Peter Krapp. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011), 64. ↩

-

Benjamin, Arcades Project, 204. ↩

-

Ibid, 206. ↩

-

Briet, 16; emphasis in original. ↩